It’s possible that every meaningful Premier League issue will be resolved by Tuesday night, rendering Sunday week an anti-climactic determination of prize money allocation for mid-table placings. Possible, but not probable though. Relegation slots may be cemented this weekend, but Man United will need a Lazarus-like recuperation to prevent Arsenal taking the title race to the wire. Once again, the Prem has delivered. And once again the majority of teams will feel they have fallen short.

PSG, Inter, Real Madrid, and Bayer Leverkusen have each secured their domestic league titles already. It’s not always these specific teams, but the narrative of early closure in France, Italy, Spain and Germany is familiar. Of the top five leagues in UEFA’s rankings, only England’s usually delivers extended jeopardy at either top, bottom or both ends of the table.

Football ownership and fandom is an enduring exercise of hope and ambition trumping realism. Hence the widespread, gnawing sense of frustration at season’s end. Who to pick as the greatest underachievers and/or most disappointing? Chelsea after spending a billion pounds on players, Spurs in their billion pound stadium, Brighton whose manager looks to be agitating to get away, West Ham who’ve told their manager to go away, Sheffield United for not giving it a proper go, Liverpool for falling for the quadruple fairy tale narrative, or Man United for, well, being Man United?

Last year’s three promoted clubs are now clear favourites to return straight back to the Championship. They began the season given the same tag by most pundits. The docking of points from Everton and Forest has tightened the equation but not, it seems, changed its answer. With six matches left between them, the three bottom clubs currently have just 66 points collectively.

Over the past ten years, the final points outcome for the three relegated teams has ranged between 77 and 98. The flip side of the top teams racking up more points season by season is fewer garnered by those in the lower reaches of the table. Little wonder that the Premier League clubs have agreed in principle to a new system of financial regulation anchoring the spending by the wealthiest to an agreed multiple of the least well-off.

The Prem’s commercial value lies in its sporting uncertainty. Increase the spacing of the rungs in its financial ladder and you would likely in time reduce surprises and with it casual fandom. Clubs need only look outside football to F1 to see the dangers of a single dominant team - and this in spite of tightened financial controls designed to improve competitiveness up and down the starting grid.

Can we cut through irrational optimism to say just who are the greatest underachievers (and conversely best outperformers)? Assume for a moment that money is a (the?) critical determinant, and that there is a material degree of rationality to its application in football. Then ground size, catchment area, performances in recent seasons (so driving prize money and other revenue) and heritage (generating a wide following capable of monetisation) should all in time determine a club’s place in the pecking order.

The assumption about rational money is, of course, a heroic one. One Sheffield United fan recently repeated the well-worn claim to me that his team is owned by the only Saudi prince who seems not to be a billionaire. But even the billionaires behave in very different ways. Jim Ratcliffe has been poking around Man United’s untidy IT department - his a bottom-up approach when fans might prefer a lopping off at the top. Time will tell whether a few more cable ties can tighten a risibly porous defence.

The biggest club ground is ManU’s Old Trafford, seven times larger than Luton Town’s Kenilworth Road. The six biggest stadia in the Premier League have a greater aggregate capacity than the other 14 clubs’ grounds combined. The teams with the biggest homes generate matchday revenues around ten times those with the smallest, testament to more extensive hospitality spaces and location in bigger cities - plus the ability to build on more extensive on-field success and the cachet of corporate fan attendance that follows.

Put all of this in the blender and the greatest outperformers are plain to see. Bournemouth: comfortably in mid-table, operating from a ground with an 11,307 capacity and the lowest average matchday income in the league.

The Sport inc. prize for falling short of potential is a tougher one to decide. It would be easy to plump for Man United, but they may yet win a trophy this season and I need to filter out the joy of their 4-0 drubbing at Selhurst Park on Monday. Instead my head says Everton.

Add back the eight points deducted for breaching financial rules and Everton would still sit 13th in the league, below the scale of the opportunity afforded by their location and infrastructure, even before the club’s impending move to a new 52,866-seater stadium. Ownership uncertainty has hung like a cloud over the past two seasons. Quite how Everton’s current owners have botched selling into an apparently buoyant market for trophy clubs is beyond me - and all other observers it seems.

Only 40 days until the 2024/25 fixtures are announced. Prepare to dream once more.

Is there a doctor in the house?

Just tinkering with an algorithm for my PhD in sports nonsense to rank clubs’ respective odds on winning the league. Feel free to suggest tweaks.

(General admission capacity x (10 x hospitality seats) x (0.25 x population within 1 hour travel) x (social media followers ÷ 1 million) x (replica shirts sold worldwide ÷ ‘000k) x (major trophies won by club within past decade) x (major trophies won by manager within past five years) x (average IQ of ownership group ÷ number of people in ownership group) x (aggregate wealth of ownership group ÷ $bn)) ÷ dirty socks on floor at training ground changing room

The Brady Bunch

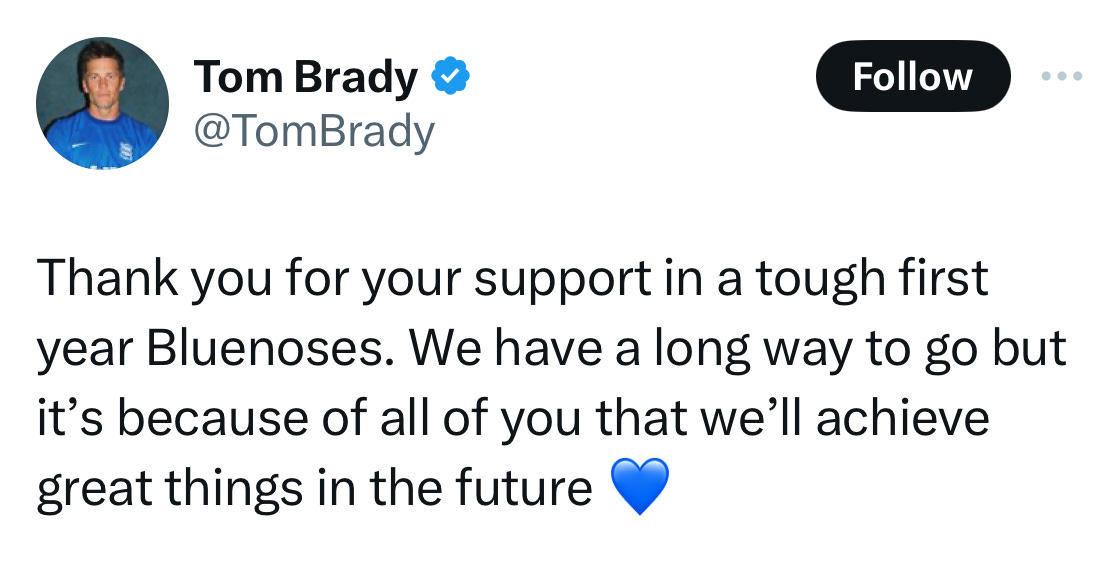

For every Premier League team there is at least one supposed sleeping giant, a club deemed worthy of top flight status by virtue of its history - even if that history dates back to bell-bottoms and platform shoes or even flat caps and rattles. The latest giant indignity is Birmingham City’s, relegated just seven months after NFL superstar Tom Brady was unveiled as an investor in the club and chair of its new advisory board.

“Tom Brady joining the Birmingham City team is a statement of intent. We are setting the bar at world class. Tom is both investing and committing his time and extensive expertise.” Birmingham chairman Tom Wagner in August

Brady played for just two teams in a 23 season NFL career, winning seven Super Bowls. Birmingham City had six different managers in the dugout this season alone. Those advisory board meetings must have been interesting.

Time Machine from Suburbia to Wembley

HG Wells, David Bowie, Hanif Kureishi, Jack Dee, Pixie Lott, Dina Asher-Smith. Bromley sons and daughters all. The town on the outskirts of London rustled up more than twenty thousand supporters at Wembley to see Bromley FC promoted to the Football League for the first time in its 132 year history. Not yet a sleeping giant, but a population of 330,000 in this relatively affluent London borough might yet stir the imagination of a Saudi prince with a few petrodollars to spare…

Tom and Karren Brady. Doubly cursed.