It’s a pity Emily Bridges was blocked from competing in the National Omnium Championships in Derby last weekend. Yes, the cyclist would have been at the centre of an unsavoury media scrum, but we would have gathered one more valuable data point with which to try and balance the febrile debate about transgender women in sport.

Cycling’s international governing body made a late intervention to prevent Bridges from taking to the track. Its ruling was technical, and may have only delayed the cyclist’s first competitive outing as a woman. But the UCI might now be using the few weeks’ hiatus as an opportunity to revisit its reliance on testosterone levels as its gauge of a cyclist’s eligibility as a female competitor. Or, as reported in recent days, to fall back on a clause in its regulations which could give it a catch-all ability to override testosterone readings.

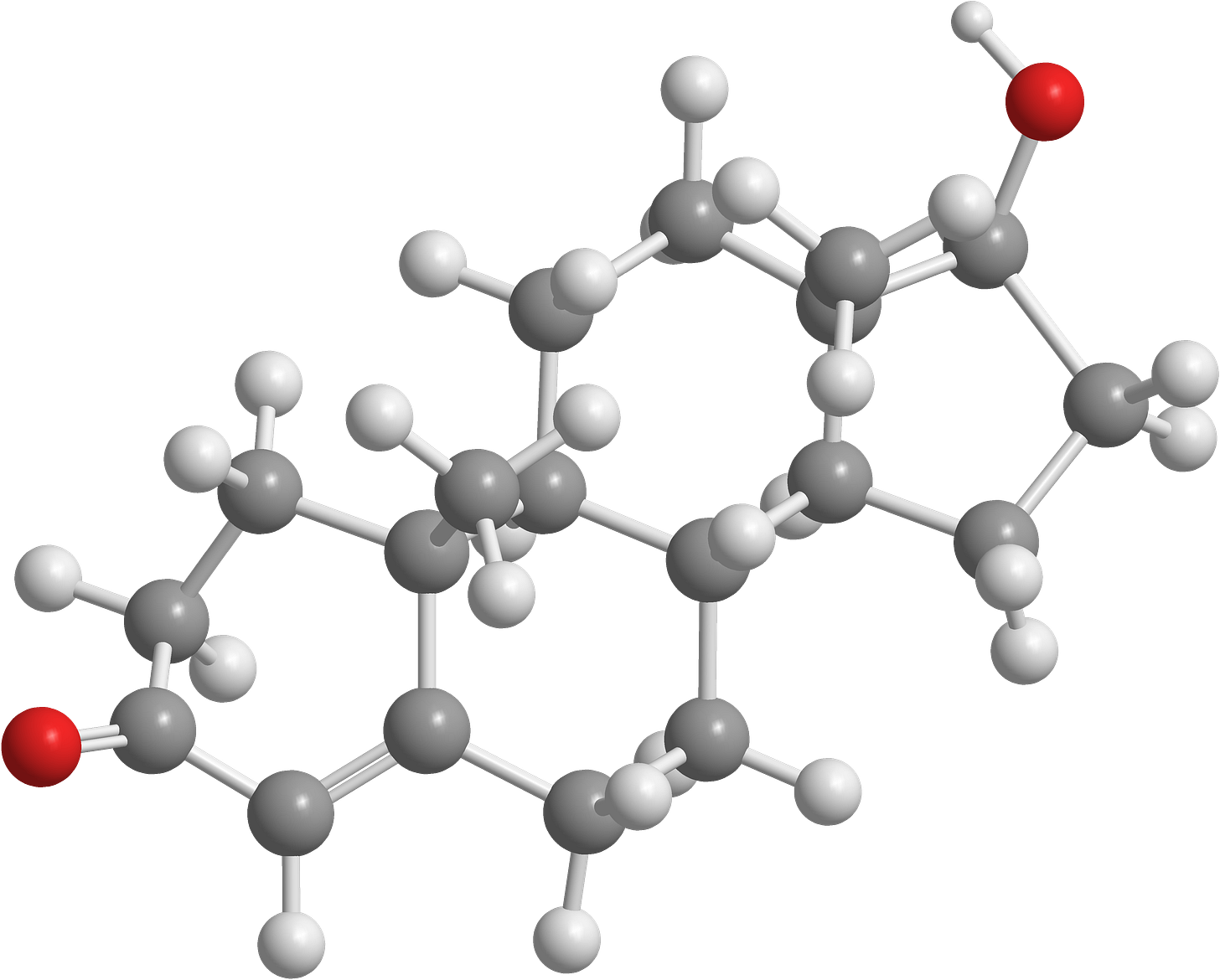

Cycling has not been alone in grasping at testosterone as the answer to the conundrum about gender identity and the definition of female sport. Although an entirely different physiological and psychological issue, athletics’ response to complaints about intersex athletes - and most particularly Caster Semenya - has helped drive a wide range of sports towards testosterone measurement. And, by extension, to the endorsement of medical interventions to supress testosterone levels.

Semenya has been in and out of the courts to challenge World Athletics’ regulations. When she took testosterone suppressants to enable her to compete, her times suffered. When she had the upper hand legally, and suppression was not required, her competitiveness was restored. World Athletics is currently in the legal ascendancy. Semenya refuses to resume ‘treatment’ and missed out on the Tokyo Olympics. Little wonder then that sports believe athletics may have found the answer to the trans moral maze in its thirteen year long intersex battle.

An answer maybe, but not the answer. For there can be no definitive answer. No outcome that will satisfy all parties. No solution that is fair to all, and will be accepted as such.

The UCI’s catch-all clause in its regulations is a requirement to ‘guarantee fair and meaningful competition’. But what is fair female competition? Open for all who identify as women to enter - and hence providing fair opportunity for all? Or only open to those deemed not to have an ‘unfair’ advantage by virtue of their birth sex - and so a fair or level playing field?

It seems to me that ‘meaningful’ will become the key word in the inevitable legal battle in the coming months and years. And yes, it will be years, given the seesaw of the Semenya precedent.

“If she’s competitive it’ll be because she’s talented, not because of her chromosomes.” Read Pippa York on Emily Bridges here

The meaningfulness of sporting competition will always be in the eye of the beholder, which gives the UCI (and any other sport with a similar fall-back) its out if it wants to exclude trans athletes. Whatever the evidence about performance diminution with the lowering of testosterone levels, male puberty appears to bestow lasting physical advantages over those born female. Any amount of data is unlikely to sway those arguing that meaningfulness of competition trumps fairness to trans athletes wanting to compete in female events.

Note too that for some sports this is much more than simply an elite issue. Non-contact grassroots sports can clearly cope with self-identified gender classification, even if that might cause grumbling among weekend runners, cyclists and triathletes. The lasting advantages of male puberty are much more than simply a question of finishing times in rugby, football and combat sports, at all levels.

I’ve written before about my sympathy for Caster Semenya, in large part generated by witnessing first hand her shabby treatment by World Athletics and the vitriol from some of her competitors. I’d allow her and other intersex athletes to compete freely in female events.

I come down the other side of the line in the debate about trans women and female sport, though. The easy riposte is that this is anti-trans, whereas it is nothing of the sort. Instead it is a realistic least-worst approach. However cycling came up with its ‘meaningful competition’ clause - whether it was ever intended exactly for this purpose - it does go to the heart of the matter.

Many, perhaps most, sports will not have such an exit route baked into their regulations. They won’t have been helped by the International Olympic Committee’s new guidelines on transgender women. These state that there should not be a presumption that trans athletes have an unfair advantage, but leave decisions up to individual sports. Leadership from the IOC as ever conspicuous by its absence.

Governing bodies need to provide competition opportunities for all. Changing male events to ‘open’ categories would be a simple way to achieve this, recognising of course that this fails to satisfy the ambitions of Emily Bridges and other trans women. Again, a least-worst solution. Certainly better than creating separate trans categories which would almost certainly never become part of the Olympics and major international championships for lack of sufficient competitors.

Come one, come all

The standout sporting contest of a typically crowded weekend was the Papa John’s Trophy final, a stirring 4-2 extra time win for Rotherham United over Sutton United. The match was played out in front of 30,688 people at Wembley - getting on for twice the combined capacity of the two clubs’ grounds and two and a half times their joint average home attendances. Proof once again of the lure of the national stadium for fans - as seen when England’s women play at Wembley.

This happened to be a big weekend for women’s sport. The cricket World Cup final in Christchurch, New Zealand. A round of Six Nations rugby. WSL football. All hard on the record crowd of 91,533 for women’s football at the Champions League game between Barcelona and Real Madrid at the Nou Camp.

The RFU is staging the Red Roses’ Six Nations matches at club grounds this year. Its counterparts have similarly opted for smaller venues. A record crowd of 4,875 watched Wales at Cardiff Arms Park rather than the Principality Stadium on Saturday. Some WSL fixtures are at their male counterparts’ stadia, but only the minority - just one of this weekend’s six fixtures.

Standards in elite women’s sport are on the rise, as are attendances. Rates of development of both differ. I can’t help thinking, however, that providing the best possible stages as often as practical will help accelerate the quality of the sport and its public recognition. Yes, it costs more to open and steward a larger venue. Yes, there is wear on playing surfaces. But 5,742 watched Liverpool win promotion at Bristol City’s Ashton Gate on Sunday. By contrast, there were only 418 at City’s previous home game played instead at the club’s high performance centre. Set the stage.

Daft draft

It’s hard to be less excited about this week’s draft for The Hundred. The absurdity of persevering with two short-form cricket competitions seems to be grasped by everyone bar the ECB itself. The Blast and The Hundred are currently head-to-head in the ticketing market, competing for scarce family cash during a cost of living crisis. Time for the counties to fight back against the ECB’s franchise experiment before their T20 product is irreparably damaged.

A challenging topic indeed with, as you say, no perfect one-fits-all solution. It will be interesting to see how the arguments develop among the differently affected sports.