You have just one day to submit your application to be the inaugural chair of the new Independent Football Regulator. Former Tory MP Tracey Crouch’s blueprint has been adopted by Labour Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy, whose professional reputation will likely be made or broken by the decisions of the IFR. Unless the customary game of ministerial musical chairs leaves a successor in her hot seat when the first controversies land.

The time for carping about the need for a regulator is past. It is an inevitability, deemed a football crowd-pleaser by politicians of varying hues. Now the battle is one of influence and financial control. Unsurprisingly, the job ad for the chair is being circulated widely by opponents of the concept of a regulator in the hope that a moderate rather than a zealot will land the role. A few people have sent it my way, but I can’t think of anything more likely to suck me dry of my love of the game. Think regulator as Dementor.

That ad cites eight essential criteria of which candidates must demonstrate they have a majority (so, not all really essential). Three of the eight reference the sport: one, an understanding of the business of football; another, influencing skills with a wide range of stakeholders including those within the game; the third, a commitment to its economic and social value.

Given the maths, I guess you could land the job on the basis of stellar regulatory, business and chairing credentials garnered in other fields, but surely any non-fans will swiftly be sifted out in the recruitment process. Imagine being in a room of footy people and not knowing your Arsenal from your elbow. Sport is a sector which has a reputation for brutally ejecting those whose knowledge is built on shallow foundations.

The third of the listed essentials reads: “a commitment to the five principles of Government’s Better Regulation Framework, with particular focus on proportionality.” Unfamiliar with all five? Me too. The other four are accountability, transparency, consistency and targeting. All worthy ideals, but show me a major regulator that has managed to operate within these five constraining principles. Especially proportionality - and here lie the greatest fears of the opponents of the IPF.

The excellent sports team at LCP - enthusiastic fans of the concept of a regulator - have flagged two intriguing issues in their analysis of the draft Parliamentary bill that will bring the IFR into being. The first is the requirement to involve the FA, which LCP views as an opportunity to reform its governance and restore its authority within the game. The second, ominously, is the apparent assumption that clubs will effectively foot the bill for the IFR.

I’ve been baffled for some time at the FA’s apparent distancing of itself from the debate about regulation. After all, if it had been performing effectively in recent years there would be no need for the creation of a new regulatory bureaucracy. Last time I checked, the FA was still the national governing body for football in England. Engineering the FA’s involvement seems a clumsy way to try and make it fit for purpose. Either it speaks with an authority that demands it be heard, or it focuses on the England teams, Wembley Stadium, FA Cup and grassroots game, leaving the thorny issues surrounding the top 116 professional clubs to others.

“If the FA is to truly be given an opportunity to reform itself, it must be allowed to actively partake in the process of governance. The offer of an independent observer role [in the draft bill] does not facilitate this. A full seat on the Board of the IFR would we believe be more appropriate.” Aaryaman Banerji, Head of Football Governance, LCP

As to funding, if the government expects those 116 clubs to carry the financial burden of regulation then it’s condemning the IFR’s leaders to a Groundhog Day of painful negotiations with the Premier League. After all, their relative financial might sits at the heart of the tussle over regulation.

You can be sure that the PL clubs will use any obligation to fund the regulator as an opportunity to grind down its scale and by extension its ability to get anything done. Expect them to query every budget line, every year. But don’t assume the 72 EFL and 24 National League clubs will be happy at being invoiced either. After all, any settlement on costs will surely have to include some payment, however small, from all parties. Otherwise, what legitimacy does the voice of non-payers have?

“The regulator risks becoming drowned in bureaucracy and billing issues in a market in which it cannot compete financially.” Aaryaman Banerji

It has been suggested that the IFR will be smaller than other regulators. The Gambling Commission’s annual expenditure, for comparison, is just over £40 million, 57% accounted for by the cost of its 363 employees. It would be no surprise to see the IFR at half that size in short order and growing thereafter as the inevitable scope creep and public sector bureaucracy takes hold. Not enormous sums in the context of a star striker’s transfer fee, but a big enough ask for the IFR chair to find him- or herself on the back foot in dealing with the Premier League.

If none of this has put you off, you have until 23:59 on 8 November to send in your CV and covering letter and brush up on the Nolan Principles in anticipation of an interview. Pays £130,000 for a three day week, so do expect the usual media carping about a pro-rata salary in excess of the Prime Minister’s. Rest assured, that won’t be the sharpest barb you have to deflect in your first term of office.

Brass in pocket

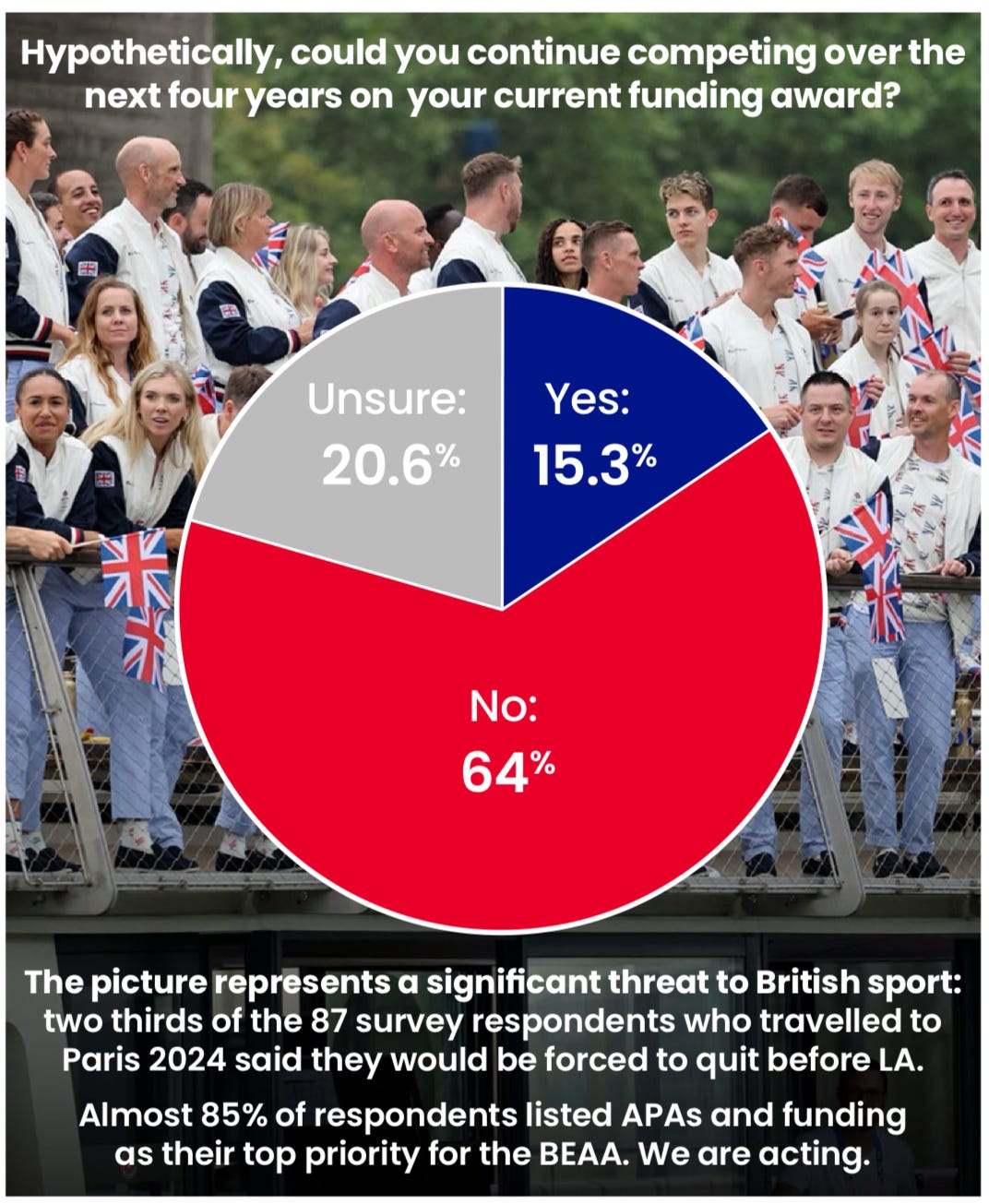

Last week I referenced both the welcome £9 million bump to UK Sport’s funding in the new government’s first budget and the concerns elite athletes have about their ability to finance their careers through to LA28. I’ve gleaned more insight on these fears from the British Elite Athletes Association which represents GB’s Olympians and Paralympians.

The top level of funding available to an athlete is £28,000 a year. It is tax free but means tested, so those with sufficient alternative income aren’t eligible for this Athlete Performance Award (APA). This sum has not changed since London 2012. The BEAA estimates that the average full-time athlete in receipt of funding receives a maximum of circa £22,500 - the equivalent of a pre-tax salary of about £26,500 on Civvy Street.

If APAs had risen in line with inflation over the past twelve years, those in the top band would now be in receipt of just over £39,000 a year. This is 40% above the current frozen level.

Still not bad, you might say, for people competing in minority interest sports that only cross mass consciousness every four years. But training costs rack up, some athletes have families to support, and when those quadrennial Games come around the nation always expects success and revels in it when it happens. There has to be a sensible value placed on chasing medals and we can’t expect athletes in the modern world to conjure them up without decent backing.

UK Sport will be acutely aware of the strain on athletes, and very sympathetic, but no doubt has many calls on that additional £9 million a year. Catching up on 12 years of inflation for the 1,100 or so funded athletes would largely soak it all up. Devoting a meaningful chunk of the uplift received from the Treasury to boosting APAs would go some way to heading off the risk that athletes drift away from their sports leaving us all emotionally poorer in 2028.

One other point I would make about APA grants for Olympic and Paralympic athletes is that without a meaningful uplift we risk having only athletes whose friends and families can afford to support them privately. This raises the question of inclusion and access to talent throughout society.