Another international break in the football calendar. Time for managers to fret about risk of injury to ‘their’ players while away on national duty. Chairmen too to worry about heads being turned by rival club gossip in dining rooms, treatment rooms and changing rooms. Seven games in and the Premier League’s pattern is set for this season. Or is it? Just 75 days until the next transfer window opens, and with it opportunity for every club to try and turn the tide of its performance.

For all the wealth washing around the game’s stars, footballers are mere chattels. Their freedom of movement is restricted to a degree that would cause uproar in pretty much every other line of work. Long contracts provide financial certainty in a perilous profession: after all, a career’s end is always just one bad tackle away. In return for security, players give up the right to ply their trade wherever they choose. They find themselves saleable assets, their market values not only the subject of public scrutiny but the source of profits and losses for the clubs that ‘own’ them.

This month’s ruling by the European Court of Justice in a legal action by former Lassana Diarra challenging FIFA’s regulations has been hailed by some as heralding a weakening of the contractual ties that bind professional footballers. This dispute stretches back over nine years and its apparent conclusion comes almost three decades after the seminal Bosman ruling which ensured players are entirely free to play where they like once their contracts end. The Diarra outcome suggests that in future it might be easier - and cheaper - for players to break those contracts.

Just as it took years before running down a contract became a common ploy in football agents’ playbooks, so the consequences of Diarra’s case will likely take some considerable time to become apparent. It seems a good bet though that power will shift further away from clubs towards players (and their advisors). Which is surely as it should be. Regardless of the sums involved, no-one deserves to be treated as a commodity in any industry. The question for employers and the game’s authorities is where the contractual line is that they could and should try and defend.

The integrity of season-long sporting competition requires a high degree of continuity of composition of clubs’ squads. Some freshening up every January might provide exciting narratives - and give hope to seemingly lost causes - but wholesale changes to teams mid-season would risk undermining the brand integrity of the sport. Time perhaps to limit mid-season squad turnover to, say, two changes?

What though of season-to-season continuity? Long contracts - typically four or five years at the top end of the sport - give clubs strongish foundations on which to plan. Not rock solid ones though. Already, a couple of years remaining on a player’s contract has become the typical trigger point for renegotiating terms and/or the club seeking a sale while their asset retains a material transfer value. Only a year to go and power resides largely with the player, provided they are confident of their likely employability twelve months out.

If players in future find it easier to show just cause in breaking contracts, then clubs will find themselves subject to shock write-downs of balance sheet asset values to reflect disgruntled stars who successfully agitate to find new clubs. Transfer values in this world would be even more ephemeral. Rather than simply reflecting market clearing prices to satisfy willing buyers and sellers, players might find they have a direct voice in setting those prices - all with a view to maximising their own incomes.

The best employers, measured as in all industries by working conditions as well as wages, will be able to secure squad stability. After all, being well paid in a winning team is an attractive proposition for any player. For the majority of clubs, however, player turnover will likely increase further over time.

The risk for clubs is that this trend could accelerate if the grounds players are deemed to be able to use to break contracts widen. What if, for example, a manager’s unwillingness to use a player often is deemed damaging to their long-term employability in the industry? Might simple lack of minutes on the pitch become a basis on which a footballer could tear up their contract and head out the door without any financial comeback?

What too of management behaviour that would be deemed unacceptable in most workplaces but is shrugged off on football’s training grounds? Easy to imagine a claim of bullying as the basis for a player to walk away legally unshackled. An out-of-favour star forced to train with the U23s is no longer simply a public humiliation but a ‘get out of contractual jail’ card.

Transfer fees are a tax on players, diverting money from their pockets ostensibly as a reward to clubs for their talent development. Stellar fees for superstar footballers make headlines, but in years to come we may look back on them as a quirk of history, a function of a (lengthy) period in football’s power struggle between its athletes and those who employ them in the pursuit of glory and gain.

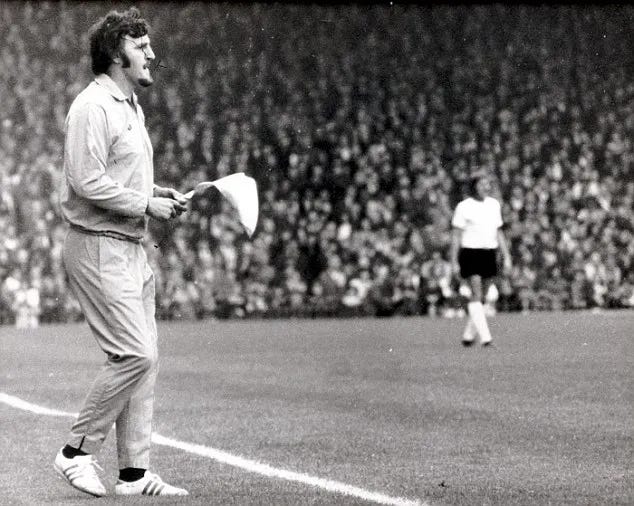

Jimmy Hill led the campaign to abolish English football’s maximum wage that eventually succeeded in 1961. I was in the crowd at Highbury to see Arsenal play Liverpool in 1972 when the former player left his TV commentary position to run the line in a bright blue tracksuit after an injury to one of the linesmen. Truly a man of many talents.

You’ll enjoy this clip of Hill taking to the pitch, as well as this one of him discussing the incident on The Big Match (check out those opening credits too…)

Noble art

You’ve just three days left to see the Expressionists exhibition at Tate Modern. Most will go for the works of Wassily Kandinsky as well as Franz Marc’s extraordinary Tiger, but I was especially taken by Albert Bloch’s 1912-13 Prize Fight (a detail from it shown above). A perfect encapsulation of boxing’s appeal across the social classes or conversely of the social stratification it has long represented. Take your pick.